Language: Mandarin Chinese

Source: Classical literature

Description

The yǎnyuèdāo (偃月刀) or "reclining moon blade" is an iconic Chinese polearm consisting of a large blade with an accelerated curve near the tip and a spike at the back.

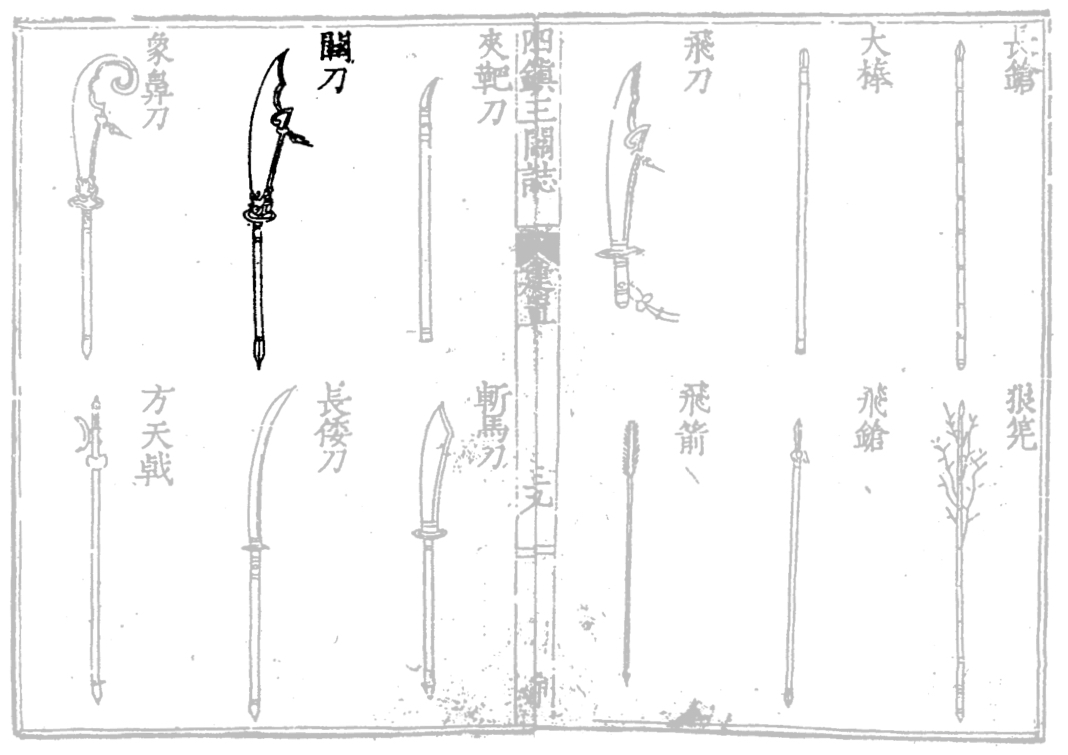

Ming woodblock illustration of a yǎnyuèdāo.

From Chóuhǎi Túbiān (籌海圖編) by Ruozeng Zheng, 1562.

The weapon has went by many names throughout the course of history, including:

Yǎnyuèdāo (掩月刀): The 11th-century name used in its first appearance.1

Guāndāo (關刀): Appears in a Ming source of the late 16th century.2

Dàdāo (大刀): In some Ming military and martial arts treatises of the early 17th century.3

Chūnqiūdāo (春秋刀): In some Qing military regulations of the 19th century.4

Qīnglóng yǎnyuèdāo (青龍偃月刀): A mythical version of the weapon wielded by Guan Yu in Romance of the Three Kingdoms.5

Eonwoldo (언월도): Korean name.

Yem nguyệt đao (偃月刀): Vietnamese name.

Notes

1. Wujing Zongyao (武經總要) or "Complete Essentials for the Military Classics" written between 1040-1044.

2. Liu Xiaozu; Sì Zhèn Sān Guān Zhì (四鎮三關誌) or “Record of four Towns and three Passes”, published between 1574 - 1576. The author was deputy commander of an important northern strategic outpost along the Great Wall.

3. Jing Guo Xiong Luo (經國雄略) of 1585, and Cheng Zi Yi (程子頤); dàdāo (大刀), published in the Wubei Yaolue (武備要略) of 1636. Chapter 8.

4. Gongbu Junqi Zeli (工部軍器則例) of 1815.

5. Sanguozhi Tongsu Yanyi (三國志通俗演義) or "The Romance of the Three Kingdoms". Attributed to Luo Guanzhong who lived somewhere between 1315 - 1400. The first official printed edition of the work was in 1522 with a preface date of 1494.

Use

According to Cheng Zi Yi (程子頤) the weapon was the general's weapon, primarily suitable for use on horseback and unsuited for the foot soldier. It required great strength and a fast horse to use effectively.1

Mao Yuanyi (茅元儀), himself a naval commander, wrote in the Wǔbèizhì (武備志): “When displayed in practice the yǎnyuèdāo is imposing, but it is not practical for actual combat.” 2

By the Qing, the use of the yǎnyuèdāo indeed seems to have been reduced to almost purely ceremonial. Yǎnyuèdāo were often carried by the retinue of high-ranked officials. A particularly heavy example, the wǔkēdāo (武科刀) was used for strength training and strength testing in the Qing military.3

Ming mounted soldiers depicted with their yǎnyuèdāo.

From the "Departure Herald", Jiajing period reign (1522–1566)

National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Notes

1. Cheng Zi Yi (程子頤); dàdāo (大刀), published in the Wubei Yaolue (武備要略) of 1636. Chapter 8. Also see Jack Chen's translation at www.chineselongsword.com.

2. Mao Yuanyi (茅元儀); Wǔbèizhì (武備志) or "Treatise of Military Preparedness". 1594.

3. See among others Huángcháo Lǐqì Túshì (皇朝禮器圖式) or "Illustrated Regulations on the Ceremonial Paraphernalia of the Dynasty", edited by Yun Lu. 1766 woodblock edition based o a 1759 manuscript. Chapter 15. It mentiones both the yǎnyuèdāo and wǔkēdāo. A detailed description of the wǔkēdāo in the examinations can be found in Etienne Zie; Pratique des examens militaires en Chine. Zi. Imprimerie de la Mission catholique, 1896.

History

First appearance in the Song dynasty (960 – 1276)

The weapon first appears in the Song dynasty Wujing Zongyao (武經總要) or "Complete Essentials for the Military Classics" written between 1040-1044. The woodblock illustration already shows the weapon in its mature form, but we must remember that the earliest version that has survived is a 1510 reprint, possibly with later woodblock images.1

Here, it is called yǎnyuèdāo (掩月刀) with a different first character, also pronounced yǎn. It means "to cover up". Literally, it would translate to something like "covered moon blade". Both are references to the crescent moon.

Association with Guan Yu

Today the yǎnyuèdāo is primarily known as the guāndāo (關刀) after its supposed use by the famous general Guan Yu (160 - 220 A.D.) of the Three Kingdoms period (220–280 A.D.) However, the first appearance of the weapon in art or literature doesn't occur until some 1000 years after Guan Yu passed away.

It was the historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a mix of history, myth, legend, and fiction, where Guan Yu is first described with a large weapon named the Qīnglóng yǎnyuèdāo (青龍偃月刀) or "Green Dragon Reclining Moon Blade" that weighed 82 catties, or about 18 kilograms.2

The earliest depiction of Guan Yu with a yǎnyuèdāo currently known to me. It is carried by the man on the left.

The earliest depiction of Guan Yu with a yǎnyuèdāo currently known to me. It is carried by the man on the left.

By Shāng Xǐ (商喜), imperial court painter of the Ming. First half 15th century.

Hanging scoll, ink on silk. Palace Museum Collection, Beijing.

Guan Yu was deified as early as the Sui dynasty (581 – 618) as a symbol of loyalty and righteousness. He later became canonized as the God of War, and by the Qing dynasty, as many as 200 temples were erected for him alone that were mostly frequented by soldiers.3 Manchu soldier Dzengseo, who campaigned in the 17th century under Kangxi, mentioned in his diary that they burned incense for his image before going out to war.4

Ming dynasty (1368-1644)

Various military treatises of the Ming dynasty mention the yǎnyuèdāo, now all except one using the characters 偃月刀. There is one exception. The Sì Zhèn Sān Guān Zhì (四鎮三關誌) or “Record of four Towns and three Passes” of 1574 - 1576:

It is the only historical work I know of that calls the weapon a guāndāo (關刀), after Guan Yu, confirming that the connection between the yǎnyuèdāo and Guan Yu was now firmly lodged in the minds of some military men.5

Some other mentions in the Ming:

1562 Chouhai Tubian (籌海圖編)

Or "Illustrated book on maritime defense" by Zheng Ruoceng 鄭若曾 (1503-1570).

1585 Jing Guo Xiong Luo (經國雄略)

This work was written by the uncle of Zheng Chenggong. It contains a section on the use of the yǎnyuèdāo as well as its construction. Notice that the shorthand dàdāo (大刀) or "great sword" is now also in use, a term that would start to denote an entirely different weapon in the 20th century.

1632 Wubei Yaolue (武備要略)

This military treatise illustrates a form with the yǎnyuèdāo. Notice that here the yǎnyuèdāo and zhǎnmǎdāo (斬馬刀) are now both categorized under dàdāo (大刀). The term yǎnyuèdāo still appears in the text.

Qing dynasty (1644-1912)

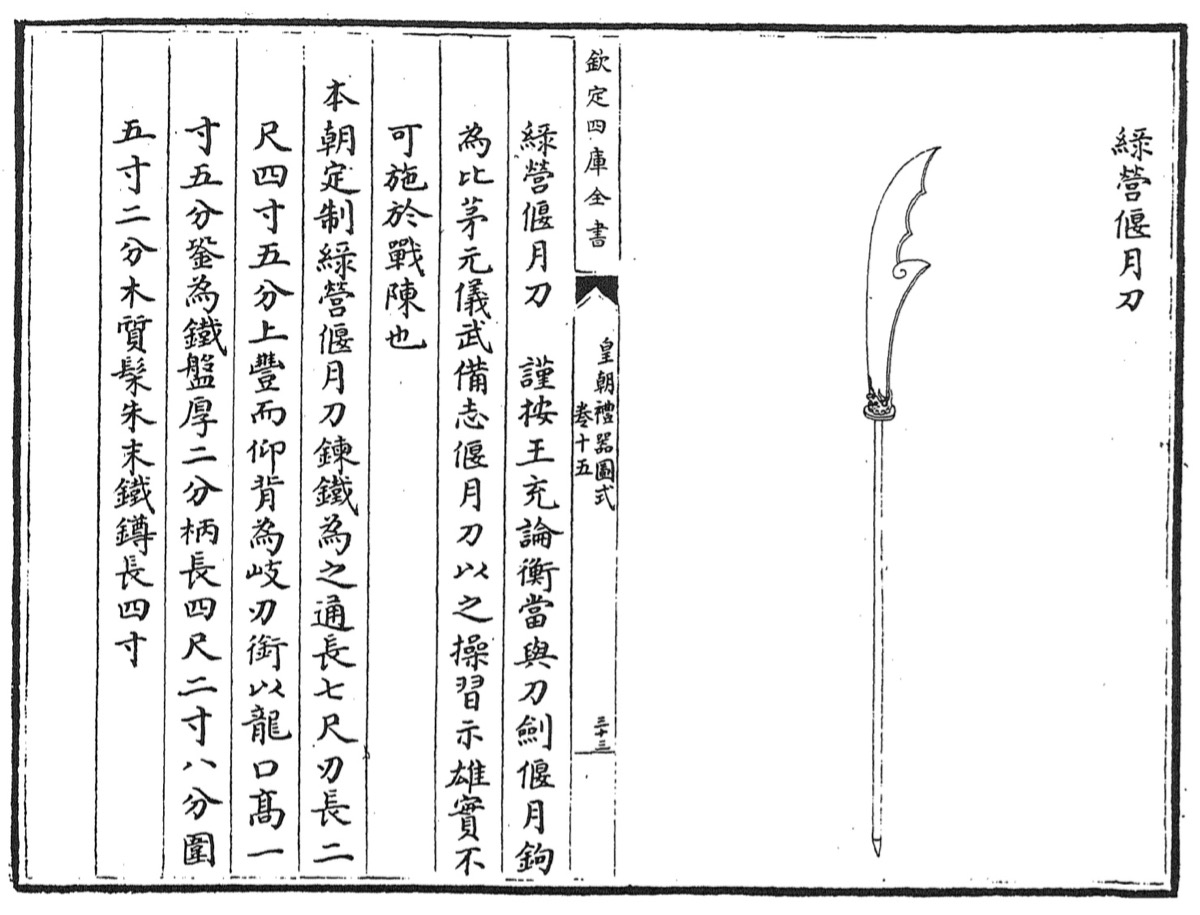

During the Qing, the yanyuedao is listed among others in the 1766 Huangchao Liqi Tushi (皇朝禮器圖式) or "Illustrated Regulations for the Ceremonial Regalia of the Present Dynasty" that was in turn based on a 1759 manuscript. It was listed as being used by the Green Standard Army, the all-Han army under the Qing dynasty that were a remnant of the old Ming army that mainly used traditional Chinese weapons.

GREEN STANDARD ARMY YANYUEDAO

"According to:

Wang Chong’s CRITICAL ESSAYS :

“In supporting those with swords and sabers, reclining moon hooks do comparatively well.”

Appeared in the TREATISE OF MILITARY PREPAREDNESS:

“When displayed in practice the yanyuedao is imposing, but it is not practical for actual combat.”

The regulations of our dynasty:

Made of forged iron [as to produce steel]. Overall 7 chi long, the blade is 2 chi 4 cun and 5 fen. Blade has a substantial tip that curves upward. The back of the blade has an edged spike. The blade is held in a dragon mouth shaped collar that is 1 chi and 5 fen high. It has an iron disc guard that is 2 fen thick.

The handle is 4 chi 2 cun and 8 fen long with a 5 cun and 2 fen long sleeve. The handle is made of wood and lacquered vermillion. At the end is an iron pommel that is 4 cun long."

The chūnqiūdāo (春秋刀) or "spring autumn blade"

From the 18th century to early 19th century, various texts have been produced in attempts to standardize Qing military arms manufacture and maintenance. One of the challenges of Qing military logistics was that weapons went by different names in different provinces, and that by the same name not always the same item was meant.

The Qīndìng Jūnqì Zélì (欽定軍器則例) or "Imperially commissioned regulations and precedents on military equipment" and Qīndìng Gōngbù Jūnqì Zélì (欽定工部軍器則例) or "Imperially commissioned regulations and precedents on military equipment for the Board of Works" are two such legal texts that regulate the manufacture and maintenance of military equipment.

The Qīndìng Jūnqì Zélì mentions yǎnyuèdāo and chūnqiūdāo (春秋刀) seemingly interchangeably. The Qīndìng Gōngbù Jūnqì Zélì sheds light on the matter: It only treats the chūnqiūdāo but describes its manufacture in such great detail that we know it to be identical to the yǎnyuèdāo as it appears in the Huangchao Liqi Tushi (皇朝禮器圖式).

Left a page from the 1766 Huangchao Liqi Tushi.

Right a page from the 1815 Junqi Zeli.

Long story short, chūnqiūdāo is synonymous to yǎnyuèdāo in the Qing, and it was a name apparently used enough to use it in official texts dealing with manufacture. This may seem strange, but even the simple saber went by two different names, yāodāo (腰刀) and pèidāo (佩刀) where pèidāo seems to be used more by the upper classes and the name yāodāo is more commonly used in texts dealing with arms manufacture, distribution, etc.

Wukedao

During the Qing dynasty, exceptionally large and yǎnyuèdāo, called wǔkēdāo (武科刀) or "Military Exam Blade" were used for strength training and strength testing. In order to pass the exam, each candidate was to perform a simple form with a wǔkēdāo. The standard exam wǔkēdāo was 120 jin or approximately 72 kilos but various other weights were in use for regular training purposes.

One of these heavy wǔkēdāo is currently in the Purple Cloud Temple in Wudang, being presented as Guan Yu's actual weapon. The size and weight, to some, confirms the incredible might of Guan Yu. In reality, visitors are looking at a training implement that was wielded by common soldiers of the Qing dynasty to build up strength.

Conclusion

One of the most iconic of classic Chinese weapons, it was mainly suitable for use by cavalry but remained in use for a long time leaning for the most part on its imposing appearance.

Heavily associated with Guan Yu since the 14th century, the yǎnyuèdāo may have been known to some as Guāndāo from the Ming onwards. This name never made it to any official texts dealing with the manufacture, maintenance or cataloging of Chinese weapons, where yǎnyuèdāo is consistently used for centuries.

During the Qing, the weapon saw use by martial artists, the Green Standard Army, and for preparation of the military examinations. Among antiques, yǎnyuèdāo are quite rare today.

Notes

1. Zeng Gongliang (曾公亮), Ding Du (丁度) & Yang Weide (楊惟德); Wujing Zongyao (武經總要) or "Complete Essentials for the Military Classics" written between 1040-1044.

2. The Romance of the Three Kingdoms is attributed to late Yuan / early Ming playwright Luo Guanzhong who lived somewhere between 1315 - 1400. The first official printed edition of the work was in 1522 under the title Sanguozhi Tongsu Yanyi (三國志通俗演義) with a preface date of 1494.

3. Mark C. Elliott; The Manchu Way, Stanford University Press, 2001.

4. Nicola Di Cosmo; The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China: "My Service in the Army", by Dzengseo, Routledge Studies in the Early History of Asia.

5. Liu Xiaozu; Sì Zhèn Sān Guān Zhì (四鎮三關誌) or “Record of four Towns and three Passes”, published between 1574 - 1576. The author was deputy commander of an important northern strategic outpost along the Great Wall.