Language: Mandarin Chinese

Source: Classical literature

Dàdāo (大刀) can literally be translated to "great saber", "big knife", etc. Dà (大) simply means "big" and dāo (刀) is a very broad term that can cover anything edged from a small utility knife to a machete, saber, single-edged straightsword to a variety of edged polearms. As such, the term has been used to describe a broad range of weapons throughout history.

Today the word mostly brings to mind the iconic broad saber, a close-quarters combat weapon of post-Imperial China.

A Republican dàdāo with its original scabbard.

Sold by Mandarin Mansion in 2016.

The Warlord Period 1916 – 1928

The first pictorial evidence of dàdāo in use is in the hands of soldiers of the warlords that fought over power after the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912.

A soldier serving Christian warlord Feng Yuxiang, 1927.

The Republican dàdāo 1912–1949

In the early 20th century the dàdāo gained fame in the hands of so-called dàdāo huì (大刀會) or "Big Knife Units" that specialized in close quarters combat.

The idea behind the dàdāo is to make the cutting edge thin for low-resistance on the cut while keeping the blade heavy enough for considerable cutting power. To do this, they made the blade flat but wide, with the maximum width being behind that part of the edge that was ideally used for the cut. This flaring out gave the dadao its very characteristic shape. Designed for cutting through soft targets, it was an ideal setup in the age of modern firearms where soldiers wore minimum protection.

Various training manuals were written that describe its use:

1933 "Practical Techniques for the dàdāo" by Jin Enzhong (金恩忠)

A translation by Jack Chen of chineselongsword.com

A translation by Paul Brennan.

1933 "Practice methods for cleaving saber techniques" by Yin Yuzhang (尹玉章).

A translation by Paul Brennan.

Yin Yuzhang calls the weapon kǎndāo (砍刀) or "cleaving saber" but from a diagram in his work we can clearly see that he is describing the typical dàdāo of this period.

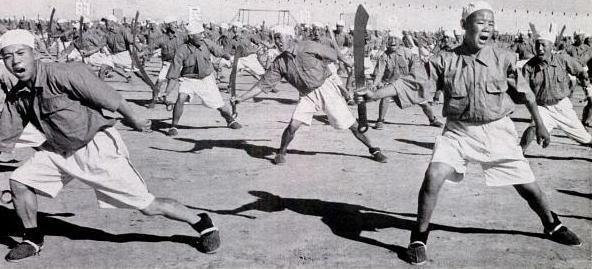

Troops training with dadao. From the article at Kung Fu Tea.

"When the Central Martial Arts Institute was established, those in the intellectual class each had their doubts, considering this to be an era of firearm warfare and that there is no necessity to encourage this antique and obsolete learning. But fortunately, due to many years of effort, Chinese martial arts has spread throughout the army so much that large saber units can be seen fighting the enemy. They charge right in, unstoppably advancing with bold shouts, like thunderclaps in the midst of a hurricane, causing the enemy to not be able to turn his horses around fast enough or have a chance to fire his guns. The blades rip open skin and sever fingers, hack off arms and pierce through chests, and within a mere ten paces, blood is already flowing enough to make a river.

Relying on modern weapons, the enemy assumed he could decisively take Shanghai in just a few hours, but was repeatedly thwarted in the streets by the large saber units. Though we should not dare to take our success for granted, the evidence of that success is at least clear, and those who said that there is nowadays no point in encouraging martial arts are waking up to the truth.

The large saber is truly a part of our martial arts. But if all of our martial arts were spread to our whole populace, just imagine the effect. Comrades and compatriots, rise up, rise up! We want the masses to be transformed by Chinese martial arts, to train vigorously to fight for our defense, overthrow imperialism, and achieve final victory!"1

Zhang Zhijiang, Shanghai, Oct, 1932

The Marco Polo incident

In July of 1937 the 219th Regiment, 110th Brigade, 37th Division, 29th Route Army lead by colonel Jí Xīngwén (吉星文) faced a Japanese troop force of 5600 men on the Marco Polo bridge or Lúgōuqiáo (盧溝橋) in Northern China.

Jí Xīngwén's men numbered about 100, carrying their dadao alongside modern rifles and grenades. Among the Japanese were cavalry armed with katana. The Japanese crossed the bridge without permission to look for a soldier that had apparently gone missing on the other side.

Soldiers of the ROC raided the bridge, dàdāo in hand, and repulsed the Japanese losing all but four men. Casualties on the Japanese side are unknown, but were high enough for them to retreat. This went into history as the Marco Polo Bridge Incident which in turn is seen as the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War. The event was a huge boost to the Chinese soldier's morale. The victory of the simple dàdāo over the mighty katana had great symbolic value.

A song called The Sword March was written in to honour the valour of the 29th Army.

The dadao has since become a symbol of the Chinese post-imperial resistance fighters, and dàdāo that carry markings of the 29th army are now highly sought after.

Soldiers of the 29th army with their dadao.

The dadao that was used by Ji Xingwen at the Marco Polo incident. ROC Museum, Taiwan.

Ji Xingwen would become a general in the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China.

He got mortally wounded by PLA bombing of Kinmen island in 1958.

Into World War 2

The dàdāo remained in service throughout World War 2.

Chinese guerrilla troops photographed near Guangzhou in 1941.

Everett Collection.

Earlier uses of the term dàdāo

Because the term is so generic, it is found to describe a number of different weapons. During the Ming dynasty the term is frequently used as a generic term for large bladed weapons on pole arms.2

Two weapons that fall under the broader category of dàdāo in the Ming are the

zhǎnmǎdāo (斬馬刀) and yǎnyuèdāo (偃月刀).

When we go back to Qing times, various weapons carry the name dàdāo. The 1766 woodblock edition of the Huangchao Liqi Tushi (皇朝禮器圖式) for example.3 It lists several variations:

Green Standard Army kuānrèn dàdāo (寬刃大刀) or "wide bladed great sword".

Green Standard Army chángrèn dàdāo (長刃大刀) or "long bladed great saber".

The same text also lists a sword that reminds strongly of the later dàdāo but without the ring pommel, but it goes by a different name:

Green Standard Army kuānrèn piāndāo (寬刃㓲刀) or "wide bladed slicing sword".

By the late Qing, dàdāo is still used to describe a large and heavy type of yǎnyuèdāo that was used for strength training and strength testing of soldiers.4

Chinese soldier holding a heavy pole arm used for strength training and strength testing examination.

Illustrated London News, 1900.

Notes

1. Written by Zhang Zhijiang, Shanghai, Oct, 1932., published in the epilogue of "Practical Techniques for the dàdāo" by Jin Enzhong (金恩忠), 1933. Translation by Paul Brennan.

2. Jing Guo Xiong Luo (經國雄略) of 1585, and Cheng Zi Yi (程子頤); dàdāo (大刀), published in the Wubei Yaolue (武備要略) of 1636. Chapter 8.

3. Huángcháo Lǐqì Túshì (皇朝禮器圖式) or "Illustrated Regulations on the Ceremonial Paraphernalia of the Dynasty", edited by Yun Lu. 1766 woodblock edition based o a 1759 manuscript. Chapter 15.

4. Etienne Zie (Siu) S.J.; "Pratique des Examens Militaires en Chine", Variétés Sinologiques No. 9., Shanghai 1896.