The enthusiast of Indian arms and armor will sooner or later hear about the Bikanēr armory. A substantial part of the armory was sold in the late 20th century to a number of UK antique dealers, and pieces have been circulating in the international antique arms scene since.

Various pieces made their way to notable museums like the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Royal Armories in Leeds, and to institutions like the Furusiyya Art Foundation, while many others are kept in private hands.

It is something that most advanced collectors seem to know about, yet an online search comes up with surprisingly little information on the armory and its importance. One of my aims is to make the world of antique arms and armor accessible to a new generation of collectors and enthusiasts, so I set out to write this introductory article to the armory and its contents.

1. Introduction to Bikanēr

2. The exploits of Anup Singh

3. Bikanēr armory markings

4. Arms and armor from the Bikanēr armory

5. Rumor has it...

Conclusion

Introduction to Bikaner

The Bikanēr armory is situated in the city of Bikanēr, which in turn lies in the former princely state of Bikanēr. I can try to draw a picture of Bikanēr but I don't expect to surpass how Hermann Goetz introduced the place to me, so I quote him instead:

"This is the Thar Desert, for millennia a no man's country, Jangaladesa, the "jungle country," crossed only by occasionally caravans of half-wild nomads. But this same forbidding desert has nurtured a tough race of brave and gallant soldiers and for centuries protected a state which has played and still plays a leading role in India: Bīkānēr. Like a Fata Morgana, its capital rises from the very midst of this desert, a great town of red and yellow sandstone, with richly decorated houses rising high over its bustling streets and tall temple spires overlooking the once mighty fortifications. Outside the town there lies a gigantic fort, surrounded by a deep ditch and a double line of mighty bastians, behind which many-storeyed palaces of yellow and red sandstone, marble and encaustic tiles tower over luxurious palm gardens."

He later continues:

"The golden age of Rājput civilization was closely linked with the destines of the Mughal Empire. As generals and governors of the emperors of Delhi, the Rājput princes had not been dependent merely on the resources of their own states, but could also dispose of considerable revenues from other, wealthier parts of India. At the Mughal court the rulers of Bīkānēr had been second only to one other Rājput state, Amber-Jaipur, which they had sometimes even surpassed. For in this service it was not so much natural wealth and economic resources which counted, but manpower and courage, which were provided nowhere more abundantly than in the hard, poor desert of Bīkānēr. Also the forbidding character of the Thar Desert, and consequently its security, has always attracted the wealth of the outside world. Here the Jain and Hindu bankers and merchants whose business reached (and still reaches) over the whole of Northern India, built their houses, settled their families, deposited their treasures, and constructed temples and upāsras (monasteries). The rājās of Bīkānēr were wise enough not to scare them away by excessive exactions. Thus the cultural life of Bīkānēr, of its court and its mercantile upper class, flourished through the centuries largely owing to the treasures flowing in from other parts of India, acquired by the valour of its soldiers and the security of its capital."

As a result of its multi-cultural character, Bikanēr was home to artists and artisans from central Rajputana, Gujarat, the Mughal court at Delhi, Lahore, and even from the Deccan.

From:

Hermann Goetz; The Art and Architecture of Bikaner State, Published for The Government of Bikaner State and The Royal India and Pakistan Society by Bruno Cassirer, Oxford, 1950. Pages 17-18.

1. The exploits of Anup Singh

The Bikanēr armory is perhaps best known for the arms and armor associated with the exploits of Anup Singh. Anup Singh rose to power in the late 17th century, being appointed ruler of Bikanēr by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1669. The Mughal empire had been in a state of crisis, fighting battles against Afghan forces, facing internal strife between several states in North India, and facing a considerable threat from the Marathas in the south. Anup Singh rose to become a competent ruler and commander who was able to consolidate his rule in the northwest, which came to be recognized as a legitimate kingdom by Aurangzeb.1

Anup Singh served extensively in the Deccan, as commander, general and administrator. He lead the campaign at Salher in 1672, Bijapur in 1675. He was the administrator of Aurangabad between 1677–1678 and rose to the elevated rank of Maharaja ("great king"), in 1679. He returned to the Deccan to lead the siege of Golconda in 1687 and the battle of Adoni in 1689. Anup Singh was appointed governor of Adoni by the emperor, which he remained from 1689 to his death in 1698.2

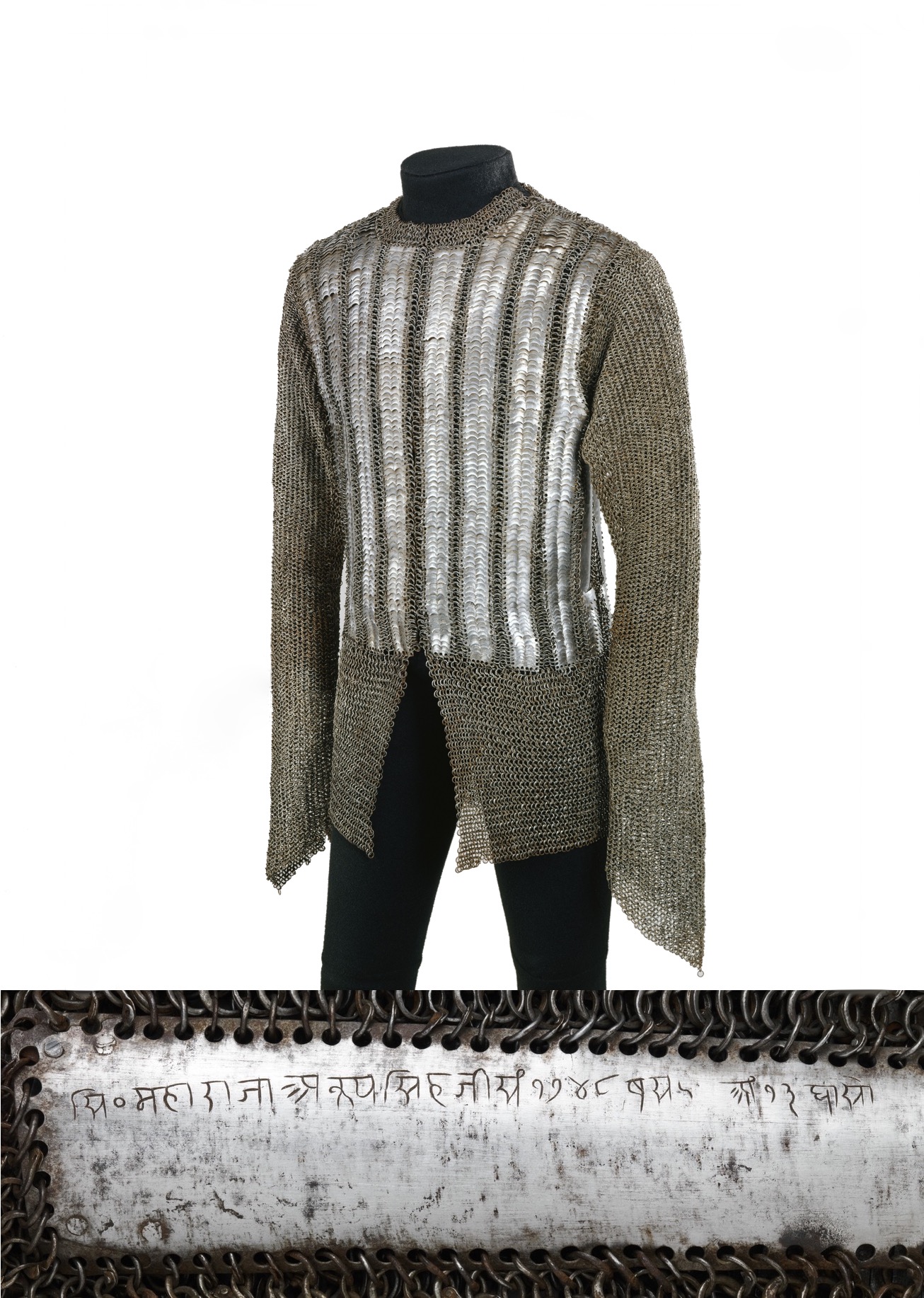

Among the booty captured during these campaigns were lots of artwork and manuscripts, which Anup Singh had shipped to Bikanēr.3 There was also a substantial amount of arms and armor captured that made it into the Bikanēr armory. Some of these pieces were inscribed with dates and places of capture, and often mention Anup Singh's name. One of the more famous of such pieces is a shirt of mail and plate in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, thought to have come from Bijapur.4

The shirt is believed to have been captured during the sieges of either Golconda or Adoni. It was inscribed with the name of Maharaja Anup Singh and the date samvat 1748 (approx. 1691 A.D.) This is perhaps the date on which it was added to the armory because no campaign corresponds to that exact year. Metropolitan Museum accession number 2000.497.

Notes

1. Hermann Goetz; The Art and Architecture of Bikaner State, Published for The Government of Bikaner State and The Royal India and Pakistan Society by Bruno Cassirer, Oxford, 1950. Pages 46-47.

2. David G. Alexander, Stuart W. Pyhrr, Will Kwiatkowski; Islamic Arms and Armor in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2015. Page 46.

3. Navina Najat Haidar and Marika Sardar; Sultans of Deccan India, 1500-1700, Opulence and Fantasy, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2015. Page 287.

4. Alexander, Pyhrr, Kwiatkowski; Islamic Arms and Armor in the Metropolitan Museum of Art Pages 46-47.

3. Bikanēr armory markings

Arms and armor of the Bikanēr armory can be identified by their characteristic punch-dot markings. The markings tend to start with what seems to be a sloppy લી, probably shorthand for the word likan meaning "entry" or "record" in old Gujarati script.

The script originated in the late 16th century in Gujarat state of northwestern India. This script became widely used for bookkeeping by merchants, bankers, and the like, where Devanagari was primarily used for literature and academic writing. With this in mind, it is no surprise that the Bikanēr armory markings are in this script.

The sides of three Bikanēr kater, with typical Bikanēr punch-dot markings.

The key to deciphering the numerals:

Arms from the Bikanēr armory often have several markings. Many items I've had in my own inventory had two or three markings. When there are three, it is very common that two of them start with the shorthand Bikanēr designation while the third is just a number, on its own. On katar, the Bikanēr numbers are usually on each of the sidebars each, while the single number appears at the base of the blade or langets. It is often smaller and done with a much finer dot punch than the other two marks.

A rare and early dagger probably Deccan and taken to Bikanēr as booty in the 17th century.

Sold by Mandarin Mansion in 2019.

It comes with three armory markings:

"Bi 123" (Left side of blade. Enlarged in picture above)

"Bi 250" (Right side of blade.)

643 (Base of blade, right side.)

A Bikanēr armory saddle axe. Of North Indian, very Persian influenced style.

Sold by Mandarin Mansion in 2017.

This weapon was probably manufactured in Bikanēr. It comes with two markings: "Bi 62" on the left side and a more elaborate marking on the back. I find the top section hard to decipher but the bottom says: "Bi 5".

Another identical axe was recently auctioned in the USA. It had "Bi 34" on the left side, a similarly elaborate marking on the back ending with: "Bi 2".

3. Arms and armor from the Bikaner armory

The Bikaner armory was situated in Chintamani fort, known from the early 20th century onwards as Junagarh or "Old Fort", where a large part of the arms is displayed today. Stefan from www.vikingsword.com was so kind as to post a comprehensive picture report of his visit to the armory here.

According to Goetz:

"Bīkānēr has one of the finest and most comprehensive collections of ancient arms in India, comprising excellent Mughal, Rājput, Deccanī, South Indian, Arab, Abyssinian, Turkish, Moroccan and even some European specimens, most of which have been collected in the course of the late 16th and 17th centuries. It is now housed in the Sūrat Bilās apartments of the Fort Palace, though some pieces have been transferred to the museum."1

He continues:

"On battle sword hilt, crossbar, guard, and pommel are heavy and plain; famous for their size and weight are the swords of Anūp Singhji's gigantic brother, Paādam Singh. In 18th century pieces the blade is frequently of the old Hindu type, but inscribed in letters of gold-wire and its neck and one edge strengthened by a cover damascened in gold. For Kattārs, spear heads, elephant goads (ankūs) and long battle axes, however, damascening came into fashion considerably later. For these national Rājput weapons the beautiful cut steel of the early Rājput arms continued to be the favourite decoration, enriched by motifs borrowed from the Deccan or taken from contemporary Rājput miniatures, hunting or battle scenes, or images of the Devi, the mistress over death and war. Mughal motifs infiltrated only slowly, used by the side or as adaptions of earlier Rājput ornament. During the later 17th and even most of the 18th century, the use of damascening was only complementary to cut steel and probably completely damascened Kattārs were first made in Sūrat Singhjī's reign"2

While sumptuous weapons were held in the Bikanēr armory, among others lavishly decorated jade hilted daggers and such, the majority of weapons we encounter with such markings are entirely made of steel, of simple form, but very well-crafted. Most rely solely on their geometry for aesthetic appeal, the early Rājput aesthetics that Goetz mentions above.

Arms from the armory tend to come to us in a condition that would almost seem over-cleaned to the collector, but this finish is seen on almost every single piece. This leads us to conclude that the arms were very well kept, the arid climate probably helped and that they were probably regularly cleaned to keep them shiny and free of pitting.

A number of arms with Bikanēr markings that I currently own, or have owned, over the past years.

"The blades of more than a dozen of these swords are of European origin. The signatures and marks mention Italian, Portuguese, English and German smiths: Andrea and Piero Ferrara, "Atterro," "Beiro 1632," "Johannes Coll 1551," Solingen. The stock of foreign arms was considerably increased by the campaigns of Anūp Singhjī in the Deccan, especially from the booty which he collected at Adoni" 3

A south Indian katar with European blade and Bikanēr armory markings.

Currently for sale.

Notes

1. Hermann Goetz; The Art and Architecture of Bikaner State, Published for The Government of Bikaner State and The Royal India and Pakistan Society by Bruno Cassirer, Oxford, 1950. Page 123

2. Ibid 125.

3. Ibid 125. An example is the aforementioned plate and mail shirt in the Metropolitan Museum.

5. Rumor has it...

Some unconfirmed rumors that circulate arms and armor collecting circles:

1. There have been three attempts to catalog the inventory of the Bikanēr armory. This may explain the sets of three marks common on many weapons.

2. All or at least one of these attempts was done in the 19th century.

3. The records of the armories' contents have since gone missing.

Conclusion

The Bikanēr armory once held a vast amount of arms that came from all corners of the empire, sometimes even from beyond. A portion of these arms made it to the Western market from the late 19thth century onwards. Some made it to museum collections, while others keep circulating between private buyers.

Most were stamped with the typical Bikanēr markings in Gujarati script, while others had more elaborate inscriptions in Devanagari which often mention Anup Singh and a date. Most of these were taken as booty after his Deccan campaigns and sent back to Bikanēr.

Bikanēr arms are a fascinating area of study and this article is only scratching the surface of what is out there, and what there is to say about these items.

Nevertheless I hope you enjoyed this introduction, and are inspired for further study.