Language: Mandarin Chinese

Source: Period texts

Description

Lòukōng (鏤空) consists of the words lòu (鏤), "to carve", and kōng (空), "hollow". It is used to describe pierced work, openwork or fretwork.1

In the field of arms and armour it was a very popular decorative technique primarily in the 17th and 18th centuries, used on some of the best sword mounts, equestrian equipment, and fittings for belts, bow cases, and quivers.

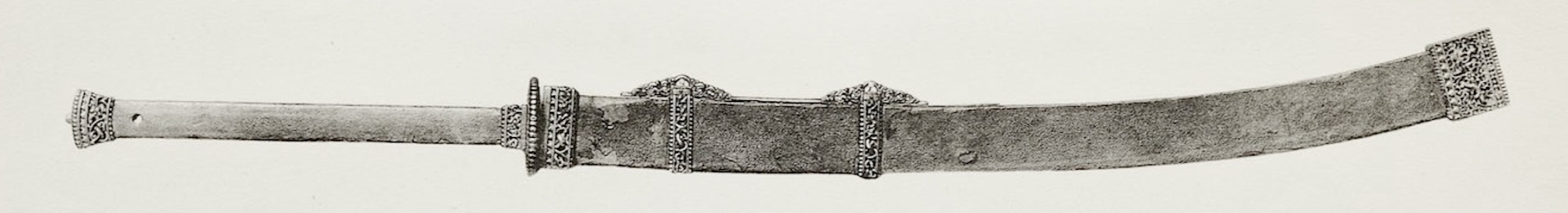

A Qing court saber of the late 18th century, with a Russian blade dated 1776.

A Qing court saber of the late 18th century, with a Russian blade dated 1776.

Executed entirely in copper alloy lòukōng mounts.

Sold by Mandarin Mansion in 2017.

Development

Pierced metalwork probably originally developed in Persia and eventually made it to Tibet where -among others- wonderful saddle plates were produced in production centers like Derge.2

This distinctly Tibetan style pierced metalwork, often with lotus petal borders and dragons among floral scrollwork, was to become the court style of the early Manchus, who would rise to become the new rulers of China under their newly founded Qing dynasty. It was perhaps popularized among them through "carved saddles" that were presented as tribute by allied Mongol tribes in the decades leading up to the conquest of China.3

Pierced metalwork was to remain in use in imperial circles and later also for the common officer, in some form until the end of the Qing dynasty.

A Tibetan saddle, thought to be Eastern Tibetan, for the Chinese market.

These are probably the types of saddles that would have been presented by the Mongols to the Manchus in the 17th century.

Metropolitan Museum, New York. Accession number: 1997.214.1

In the 17th-century

Originally lòukōng was mostly done in iron, resulting in strong and bold work that was often overlaid in silver or gold after carving. The iron pieces were forged, pierced and chiseled. The strength of iron allowed for great complexity in design, with sometimes up to three layers of tendrils passing over and under each other.

Early Qing openwork sword guards are closely related to the imperial line, from at least Hong Taiji onwards.

The saber attributed to Hong Taiji (1626-1636), one of the founders of the Manchu Qing dynasty.

Notice the double rim with lotus petals so typical for 17th-century Chinese work.

Two 17th century Chinese lòukōng sword guards.

Sold by Mandarin Mansion in 2018.

Some of these made it to Japan through trade where they gave rise to an entire genre of Chinese inspired openwork guards. They were called "Canton tsuba", presumably because they were obtained from that port. The two guards here show adjustments for Japanese use, indicating that they, too, made it to Japan where they were mounted on a katana.

Japanese craftsmen also started to make pieces in this style, called kwanto-gata or "Canton-

Oblique view of one of the guards, showing the three-dimensional nature of the carving.

Oblique view of one of the guards, showing the three-dimensional nature of the carving.

A complete Chinese imperial yidao (義刀) or "Virtuous Saber" for which such guards were made.

From the Max Dreger collection. Auctioned in 1925 and purchased by George Cameron Stone.

Bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum in 1936.

In the 18th century

From the mid 18th century onwards copper alloy became more popular, which was often fire-gilt. The later copper alloy pieces were either constructed from sheets and then pierced and chiseled, or sometimes had their basic forms cast and then worked to further detail with drilling and chiseling.

The strength of iron allowed for the greatest complexity in design, with sometimes up to three layers of tendrils passing over and under each other. The copper alloy allowed for somewhat finer work but was usually more flat in execution due to the limits of the strength of the material.

An 18th-century Chinese saber with Russian blade, in court quality mounts.

Sold by Mandarin Mansion in 2017.

The saber above represents some of the best work done in this medium of the period. It is on par with the work on some of the swords made for the Qianlong emperor himself.

Chinese saber of the turn of the 18th to 19th century.

Sold by Mandarin Mansion in 2018.

This saber is a good example of work done in the late 18th to early 19th centuries. Executed in thick brass, the designs are strong and bold and of pleasing aesthetics.

In the 19th century

By the early 19th century the most common openwork was to cast a piece close to its final shape and then pierce and chisel it out.

An 18th-century saber in what I believe are 19th-century mounts.

The style is a clear reference to earlier imperial styles.

An imperial quiver of the early 19th century.

Mounts are brass, cast and pierced and fire-gilt.

Sold by Mandarin Mansion in 2017.

Openwork mounts on a saber of the early to mid 19th century.

The fine twistcore blade is possibly earlier.

Sold by Mandarin Mansion in 2017.

As the 19th century progressed, the focus shifted more towards mass production than on the quality of each individual piece. The same can be said of European furniture with the rise of IKEA. Now, everybody could have something cool. Just don't look at it too closely. Designs were often not cut open anymore, but would simply consist of cast pieces with holes drilled into them:

A simple but sturdy late Qing officer's saber. The mounts are merely pierced with round holes.

Sold by Mandarin Mansion in 2017.

Not all craftsmanship suffered as much. Pretty nice work was still done for the guards at the imperial palace in Beijing up until at least 1900. Mass-produced, yes, but tastefully done.

A quiver of the late Qing dynasty. Obtained in China between 1908-1912.

This piece probably belonged to an officer of guardsman at the imperial palace.

Sold by Mandarin Mansion in 2019.

Notes

1. Huangchao Liqi Tushi (皇朝禮器圖式) or "Illustrated Regulations on the Ceremonial Paraphernalia of the Dynasty". Woodblock edition of 1766. Chapter 15, page 1.

2. Donald J. Larocca; Warriors of the Himalayas; Rediscovering the Arms and Armor of Tibet. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

3. Nicola Di Cosmo; Manchu-Mongol Relations at the Eve of Qing conquest, Brill, Leiden, 2001.